A remarkable achievement of the evidence-based Nay reasoning is that it has provided a solid foundation for the Jain world view. It is said that Mahaveer argued against about 363 points of views about the workings of the world mediated by supernatural entities of the various descriptions. He further suggested that each organism is the decision maker and doer and therefore also responsible for its actions.

Continuous presence of the Jain thought and practice with its distinct identity in India has been sustained for the last 5000 years by a minority (less than 1%) of the population. Its belief system emphasizes behaviors rooted in reality (sat). It is reorganized and revitalized from time to time by the bold and courageous ones (arihants) who challenge hegemony of prevailing beliefs and status quo and introduce viable ideas and practices for reform. They are recognized later as Tirthankar for the contributions that prove to be mile-stones. The last (24th) Tirthankar Mahaveer (599-527 BC) emphasized that nonviolent ethical behaviors are rooted in the reality of living organisms. It underlies cycles of actions (karm) and consequences (phal) through which organisms learn to modify their behaviors for their success. Identity (atm as adjective, and not atma noun) of an organism emerges from the quality of behaviors (gunasthan) perfected through own efforts rather than subservience to divine grace.

Ideas of Mahaveer were orally transmitted and developed by eight successive leaders (Gandhar) of the original group that flourished for the next 200 years in Bihar (Nor-East India). Social and economic upheavals in the region prompted the eighth Gandhar Bhadrabahu to move the original group. It is said that some 40,000 monks and their followers moved to the South and West (ca. 350 BC). In all likelihood the move saved the tradition from extinction, however it disrupted the oral tradition and only parts of the teachings and practices (achar) were transmitted through successive generations. After the writing technologies acceptable to the tradition of non-violence became available some 400 years later the available fragments (conceptual terms, sutr, gatha, and incomplete texts) were assembled in written form. These manuscripts on naturally dried palm leaves with characters are scratched and made visible with soot survived several centuries during which their copies were disseminated to other geographical regions. These written works served as nucleus for enormous creativity to comment, interpret, reconstruct and extend the ancient thought processes. Copies of such works with intact ancient text were also made. Copies of copies in the later centuries were made on paper which is less durable and required more frequent copying. Through the efforts of dozen of traditional scholars in 20th century the Prakrit and Sanskrit texts of most of the ancient manuscripts with translations and commentaries in modern languages are now available in printed form and photocopies ( http://www.jainlibrary.org/index.php ). It should provide stimulus for the future works to understand the ancient thought processes.

Mahaveer refuted the prevailing forms of theism. During his first discussion with Gautam (a scholar of Brahminical theism) he observed that organisms do what they do, do so for their own well-being, bear consequences of their actions, learn from the experience, and change their behaviors ( Muni, 1990 ) . Diversity of actions and behaviors of organisms suggests that they are unlikely to be guided by a supreme entity. By some accounts, at the time of Mahaveer there were 363 different ways to conceive and rationalize such faiths, beliefs and world-views, which about 1000 years later were consolidate in four theistic and two non-theistic (Jain and Buddhist) philosophies ( Jain, 2000a ) . Gautam was persuaded and he joined the group of Mahaveer to later become its discussion leader. Gautam’s Nyay Sutr ( Gangopadhyaya, 1982 ; Gautam, ca. 500 BCE ) , the rules of discourse to resolve (apvarg) concerns about objects and experiences, became one of the most influential works of all time. Mahaveer’s reasoning and logical basis for atheism were further developed by Samantbhadra in 2nd century AD ( Mukhtar, 1925 , 1967 , 1977 ) , Siddhsen Divakar in 5th century ( Mukhtar, 1965 ; Sanghavi and Doshi, 1923 ) , Akalank in 7th century ( Jain, 1944 , 1970 ) , Hemchandr in 11th century ( Hemchandr(a), 1088-1172 ) , and Gunratn in 15th century ( Jain, 2000b ). Other ancient works used these insights to develop secular code of conduct for Jain monks and laity ( Jain, 1988-98 ). Interpretative English translation of some the original works relevant to the theme of Jain atheism are available on www.Hira-pub.org . A limited number of the key concept terms and the original works are cited here. Secular scholars ( Dasgupta, 1922 ; Hiraiynna, 1932 ; Roy, 1984 )have also discussed salient features of Jain atheism and its influence on Indian thought and practice. These ideas for example influenced the non-violent movement for non-cooperation with colonialism ( Gandhi, 1942 ) has become a model for social reform in the form of peaceful nonviolent protest under wide-ranging conditions.

Behaviors of organisms evolve by trial and error from outcomes of their actions and interactions. Successful behaviors contribute to sustainable survival in harmony with their environment. All organisms tend to avoid death for example by fight-or-flight response, which also encourages them not to repeat same mistakes. Humans also learn by trial and error to distinguish good and evil outcomes of far-reaching consequences. It requires evaluation of the meaning and significance of actions. Behaviors that prove to be reliable guides for the future outcomes become part of shared knowledge that improves quality of life for all. Social and biological histories are also littered with unsuccessful outcomes of irrational behaviors and dead-end practices based on barren ideas.

Empirical core of the Jain thought and practice builds on the assumption that each individual organism is guided by its own action-consequence cycle where commitments and actions (karm) have binding (bandh) consequences (phal). Proscriptions of Mahaveer against violence, lying, stealing, illicit relations, and hoarding pave the way for individuals to develop their own identity with a sense of ethics to deal with moral questions (Dharm). Codes of conduct appropriate of stages of life also nurture personal, social and universal identities (antar-, bahir- and param-atm). The social contract articulated as live and let live includes all organisms and the resources. Sustainable survival of organisms depends on mutual interdependence (pasparo apagraho jeevanam) to assure access to sufficient (pajjatta) air, water and food, as well as freedom to explore (movement) and to express and communicate (language) sense experiences for social interactions.

Sustainable survival takes into account interdependence of organisms on each other for the use of resources and environment. Social order requires viable social contract for civil society where certain freedoms are traded for certain privileges. Individual freedoms constrained by a fair and equitable social contract also contribute towards better quality of life for most if not all. Webs of complex interrelations in such enterprises have statistical outcomes where action-consequence relations are not readily identifiable. Ignorance and indifference of facts is not uncommon. For example, harmful effects of smoking were known long before tobacco use was shown to cause lung and respiratory diseases. Environmental effects of man-made pollutants can be far reaching as in depletion of ozone layer and global warming. Corrective measures are prevented not only by personal indifference but also lack of political will. Such ignorance and denial of responsibility is exaggerated by controversies concocted to sustain discredited and dead-end ideas (jalp) such as original cause, intelligent design, will of the creator, mind-body duality, grace and judgment of the supreme to guide world happenings and workings of organisms. Mahaveer advised against such other-worldly constructs to hide ignorance and suggested that it is better to speculate with worldly analogies that others can grasp. Western atheists have effectively debunked theistic constructs ( Armstrong, 1993 ; Dawkins, 2006 ; Pualos, 2008 ; Smullyan, 1987 ) however such refutations are not sufficient to encourage a secular sense of ethics to deal with moral questions.

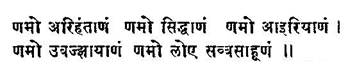

Shared knowledge . Humans interpret their experience to develop knowledge as a shared enterprise. Individuals learn through practice (vyavhar) as they grasp the underlying reality by trial and error. If encouraged to interpret, scrutinize, modify, validate, and refute they learn to make use of independent evidence. The most ancient (ca. 37 AD) of the written works of the Jain tradition Shatkhandagam ( Saha, 1965 )begins with Namokar:

and the next 23 lines (2 to 24) suggest that the investigation of an object requires characterization of its attributes which are evaluated in relation to the space-time generalizations. The quality of interpretation depends on the quality of the perception of the interpreter. The Namokar has come to represent the identity of Jain thought and practice (vangmay). It acknowledges all those who have courage to challenge hegemony of status quo (arihant) with viable alternatives, who show viability of such ideas (siddh), who formulate the ideas for scrutiny by monks and scholars (achary), and who interpret (upadhyay) and explain (sadhu) the ideas to laity (shravak). Viable ideas and behaviors evolve as they resolve concerns at different levels. The ultimate choice for action rests with the individual who has to decide to put ideas into practice. Lay followers tempted by grace or swayed by fear of judgment of make-belief gravitate towards rituals to address their concerns. As one learns futility of such articles of faith and begins to appreciate the reality of what has been done cannot be undone , the emphasis shifts towards balance (samma or samyak) and equanimity (veetrag) for rational objectivity in behaviors (thought, words, and actions). The only (keval) guide for a perfect quality of behavior (gunasthan) is to do it right first time as if there is no second chance. It leaves little room for any version of let it be so by fiat (a priori of ad hoc, nishchay) as the source of knowledge. Sustainability of the Jain tradition may be attributable to the practice that laity interprets the ideas for diversity of personal and social behaviors.

3.6.1 Saptbhangi Syad Nay(a). Just as a story improves with each retelling, certainty about a behavior also improves with experience . E mpiricism of trial and error for knowledge requires reasoning to represent and infer reality by evaluation of inputs as the sum total of the observed and measured facts. Communicating content (what, which, who) and context (where, when), and their relations (how much, far, large) empowers individuals to share and deliberate to resolve concerns about objects and experiences. Scrutiny along the way allows for better inferences for reliable action that make the future predictable, and thus the world less scary. R ational balance of instincts, emotions and expectations in behaviors bring incremental certainty to shape a sense of purpose to address concerns with a bility toevaluate consequences andtake responsibility for the outcomes . On the other hand, f ear and faith rob ability to reason to bridge the gulf between belief and behavior.

Word constructs are used to share concerns for deliberation, scrutiny and interpretation to bridge gulf between beliefs, words, and practice. Narratives build on perceptions of sense experience, but speaking your mind does not necessarily encourage deliberation to identify object or resolve concern. If common sense aligns inputs with perceptions, it takes uncommon sense of reasoning to align inferred outputs to a shared reality of phenomenal world. Scrutiny with identified content (what, who) and context (where, when) facilitates search for relations (how) to the consequences and possibly to causality (why). Certainty proves and improves by trial and error as uncertainties are chiseled away with open-ended searches. A n inference is constructed from multiple assertions, and its liabilities may be resolved with additional inputs, criteria, methods and evidence. In the same way, any search for it is (God or omniscience versus pain, air or Sun) must begin with what we know about it, and then progresses with what we do not know, and whether or not what we know or do not know is certain.

Objects and concerns exist independent of the words used to describe them. Word reasoning facilitates interpretation of the asserted content, context, and their relations. Independent evidence is required not only for such inputs but also for reasoned inference as output. Ethos, pathos and logos of reasoning with parts (Nay) are aptly captured in the parable of An Elephant and Six Blind Men where each person sees a part of the beast and interprets its reality on the basis of own experience. Of course, a better inference follows from the synthesis of the partial views in inputs, and additional inputs (anekant) may address remaining doubt (syad) in the inference. Open-ended search of a better inference moves forward by trial and error in the chaos of your word against mine .

Reasoning guided by reality (sat) to resolve concerns about object or experience requires intellectual honesty and truthfulness (satya). Truth is about speaking what one knows, and untruths are mirage (mrasha) to distract. Consider a derogatory statement by US Supreme Court justice Alito in 1991 about a person convicted of death by lethal injection, allegedly for raping a minor. As is not uncommon, this conviction was overturned in 2014 on the basis of the DNA evidence (reality). Such instances show limitations of the nature and use of evidence in the justice system, danger of being swayed by own beliefs, and need for evaluation of doubt in each judgment. Above all mistakes of violence and death penalty are irreversible. Also, no matter how the victim is exonerated or compensated, it is not possible to make up the lost time spent.

An inference (anuman) from Saptbhangi Syad reasoning derives from the logical relations of non-contradictory assertions supported by independent evidence ( Jain, 2011 ). Its basis is traced to t he suggestion made by first Tirthankar Rishabhnath (ca. 3000 BC):

![]()

i.e. a change in tangible reality (sat) is the net balance of inputs and outputs . ( Tatia, 1994 ) As conservation of matter, energy, or information it binds together the entire body of Jain thought with the logic to track reality that includes material, space, time, energy, and information. Mahaveer advised Gautam that do not while away time and effort (samayam ma gamaiye). Also the content (dravyarthic) and context (paryarthic) of the object of reasoning together form the basis of logical interpretation. Liabilities and doubt (Syad) are inherent in an inference, and more so if based on a single assertion (ekant). An inference remains tentative in search of additional inputs to resolve the remaining uncertainties, doubt and liabilities. Certainty increases with additional assertions (anekant) affirmed by independent evidence, and if the inference is also affirmed by independent evidence.

3.6.2 Inference from orthogonal assertions . Reasoning (Nay) is required to reconcile multiple assertions about an object or concern. Table 1 gives a summary of eight possible propositions for the existence of an entity asserted as: N for it does not exist, A for it exists, and U for it cannot be described . It is marked with + if affirmed and with – if not affirmed by independent evidence. Affirmation of A with sense inputs also makes it describable as sense experience which can also be subject to logical reasoning about its content and context. Affirmation of N ( it does not exist ) requires deduction to distinguish non-existence from its absence. Reasoning to affirm D (inability to describe) would also require ways to distinguish lack of sense experience from the lack of stimulus from the object.

Propositions with N, A, and U assertions affirmed (+) or not-affirmed (-) by evidence

|

|

N (does not exist) |

A (exists) |

U (un-describable) |

bit map |

|

1 |

- |

- |

- |

0 0 0 |

|

2 |

- |

+ |

- |

0 1 0 |

|

3 |

- |

- |

+ |

0 0 1 |

|

4 |

- |

+ |

+ |

0 1 1 |

|

5 |

+ |

- |

- |

1 0 0 |

|

6 |

+ |

+ |

- |

1 1 0 |

|

7 |

+ |

- |

+ |

1 0 1 |

|

8 |

+ |

+ |

+ |

1 1 1 |

Mathematical reality of the Saptbhangi propositions (Table) can be represented in the logic (Hilbert) space of the three orthogonal assertion N A and U ( Jain, 2011 ) . The cubic space of these three basis vectors has eight nodes corresponding to eight inference propositions and one of these is for the null proposition (#1). Vector-matrix algebra of representations of assertion vectors provides a basis for binary to quantum logics, logic graphs, circuits and gates. It is reasonable to suggest that similar representations of the neural networks could be the basis for the functions and theory of mind. The binary (classical Western) logic is a limiting case with two orthogonal vectors A and N in 2-dimensional logic space. With the assumption of excluded middle for the complementation of true (T) or false (F) these two scalars are connected by a line of probability. On the other hand, such formalism cannot be used to represent a d hoc theistic assertions whose consequences are not supported by independent evidence. The requirement of independent evidence to affirm an assertion is a powerful antidote against self-referential omniscience and other paradoxical constructs that have perplexed binary thinking.

Intuitive grasp of Saptbhangi requires understanding the need of independent evidence to affirm an assertion, and also of separate independent evidence for its negations. Lack of evidence to affirm an assertion is not the evidence to negate the assertion. The first (#1) of the eight propositions in the Table is without any affirmed assertion, and therefore it lacks information for further consideration. The other seven (#2 to 8) propositions have truth value of one or more affirmed assertion which together may be interpreted as consistent, undecidable, or contradictory to the available evidence. Existence of an object or concern asserted as Asti or it is (A) may for example be affirmed (+) by sense experience of its observable and measurable attributes. Affirmed Nasti or it is not (N+) is consistent with not-affirmed existence (A-). It may be challenging to affirm (N+), but it is inferred if the consequences of the presence and absence of the object in question are not distinguishable. It is conceivable that an object present everywhere is beyond the sense experience (A-) and also consequences of its presence or absence cannot be distinguished (N-). If so, such an object cannot be meaningfully described to inform its deliberation, i.e. it is a-vaktavya or it is undescribable (U+). For example consider how to describe Sun, air, pain and omniscience in terms of these three assertions.

Nothing

is indistinguishable from everything that is without evidence.

An

assertion remains valid within bounds of the independent evidence to affirm it.

Buddhist concept of Nothingness (shoonyata) is for a state achieved by

getting rid of chatter and clutter of sense inputs. It may be the ultimate

state of validity against which all sense experiences are transitory constructs

like the clouds in blue sky. Shoonyata may be a blank template (#1 in

Table) to represent reality of sense experience, but as such it is not the

reality. Also such a template can be used to represent anything one wishes

including make-believes and dreams. Akalank rebutted

shoonyata as a state

that is without a basis in the content and context of a concern. Such a self-referential

null is therefore without value for reasoning

.

Hemchandra emphasized(

Suri, 1910

;

Thomas, 1968

)

![]() (

an assertion is no different than nothing

unless supported by independent evidence).

(

an assertion is no different than nothing

unless supported by independent evidence).

Non-existents and non-issues . Complementation of false as not-true in binary logic permits the binary deduction of the true and false. ( Suppes, 1957 ) Such complementation is self-referential even with evidence (criteria) for true because lack of evidence for true is interpreted to assert false. Also true may refer to a single unique state, which will all the rest of the world not-true, that is there may be many possible false states. Arguments with a string of negations thus violates conservation of information in true to create paradoxical and contradictory constructs including omniscience (information), omnipresence (space), omnipotent (energy and force), which in essence are perpetual motion machines. Such i llogic (ku-tark) of self-reference to create impasse of your word against my word was recognized even at the time of Mahaveer and Buddha ( Matilal, 1998 ) . Such tricks are now routinely used by agencies of governments and businesses. President Bush and his senior officials waged a war against Saddam Hussein with the assertion that Iraq has Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMD) because there is no evidence that he does not have such weapons ! Cost of such illogic and words for mass deception (WMD) to US tax payers has been 750 billion dollars, and also lost productivity, infrastructure, misery, dislocation and death of millions of people .Being wrong is different than being ignorant ( Firestein, 2012 ) . There is nothing wrong about being wrong, but everything is wrong about staying wrong. Such ignorance is perpetuated with biases of wedge- or non-issues. I institutional omniscience also glosses over its own mistakes as if never happened, or deny ever being wrong, or keep the faithful guessing with inconsistencies and contradictions backed up with claims of moral high ground.

Conundrum of an atheist. Atheistic search requires courage for making real-time choices and decisions with the available knowledge that is often incomplete. It can be disconcerting because it is trail brazing without terrain map and no definite knowledge of the destination. The only reliable guide along the way is that successful behaviors do not contradict reality ( Jain, 1998 ) . Generalizations of science constrain ‘ís’ as bounds of known reality can only be a coarse guide for judgments and behaviors of individuals ( Wolpert , 1993 ) . Subjective perceptions of ‘is’ on the other hand dictate choices and shape ‘ought’ with desires and wishes ( Iyengar, 2010 ; Schwartz, 2004 ) . Such perceptions remain chaotic because what one knows in real time may not be certain, and even the best-laid future plans have contingencies. It does not mean that one should resort to fiction, fairy tales or make-belief unconstrained by reality. The atheist way is to let conscience and ethical conduct guide ‘ought’ though such uncertainties. Such empirical trial and error gives freedom to explore frontiers ( Hook, 2002 ) that provides meaning, purpose and direction, and also freedom to make fool of oneself ( Laham, 2012 ).Let buyer be beware is the caveat for a chaotic marketplace of ideas where choices become actions, actions become habits, and habits become character that shape identity.

References

Dawkins, R. 2006. The God Delusion. New York: Houghton-Mifflin Co.

Firestein, S. 2012. Ignorance: How it drives science . New York: Oxford University Press.

Gautam. ca. 500 BCE. Nyay Sutr (NyayaSutra) of Gautam (Available on http://www.hira-pub.org/nay/index.html) . Washington DC: Hira-Pub.org.

Hiraiynna, M. 1932. Outlines of Indian Philosophy . London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd.

Iyengar, S. 2010. The Art of Choosing. London: Little Brown.

Jain, H. L. 1988-98. Shravakachar Sangrah. Sholapur, India: Jeevraj Granthmala.

—. 1970. Granth Traya of Aklank (ca 750 AD).

Jain, M. K. 2011. Logic of evidence based inference propositions. Current Science, 100:1663-1672.

Matilal, B. K. 1998. The Character of Logic in India . Albany: State University of New York Press.

Mukhtar, J. K. 1925. Swami Samantbhadra. Bombay: Jain Granth Karyalaya.

—. 1965. Sammati Sutr of Siddhsen Divakar, pp. 61. Veer Seva Mandir, Delhi.

—. 1967. Apt Mimansa or Devagam of Samantbhadra (ca. 300 AD), pp. 119. Veer seva Mandir, Delhi.

Roy, A. K. 1984. A History of the Jainas. New Delhi: Gitanjali Publishing House.

Schwartz, B. 2004. The Paradox of Choice: Why More is Less . New York: ECCO.

Smullyan, R. 1987. Forever Undecided: A Puzzle Guide to Godel . New York: Knopf.

Suppes, P. 1957. Introduction to Logic. Princeton, NJ: D. Van Nostrand Co.

Wolpert, L. Six impossible things before breakfast .

—. 1993. The Unnatural Nature of Science. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press.